In the Field with Connor: Magic of the Simple Marsh

I have to admit, I didn’t expect to be waking up before the sun to come into work this summer, but the tides don’t care about your sleep schedule.

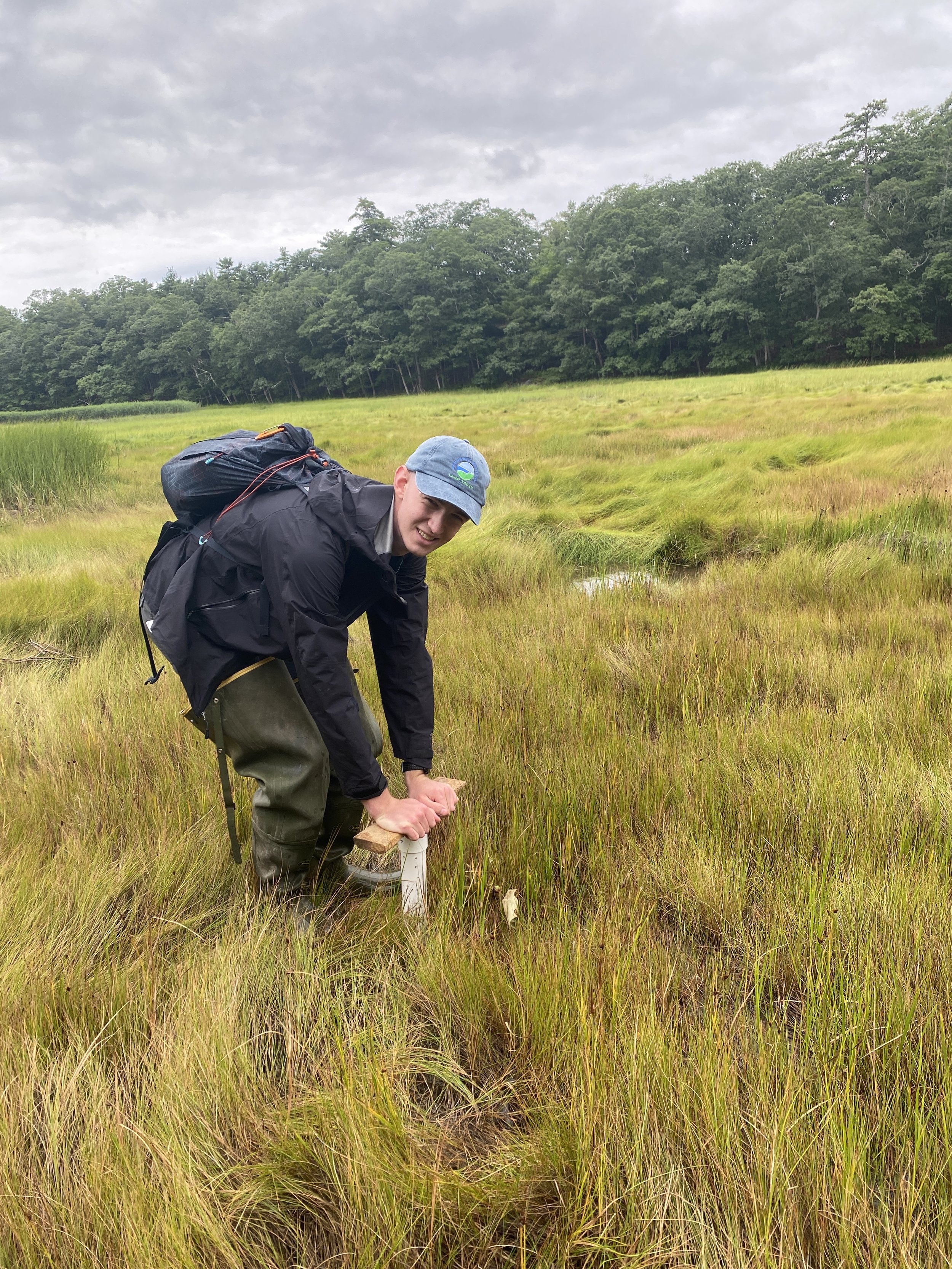

Connor trekking through the marsh!

This particular early morning found KELT’s Project Director, Ruth Indrick, and me on the way to the Little River Marsh in Georgetown. The low tide we had awoken to catch was evident as we drove to the marsh, with areas I had previously seen underwater exposed as tidal mudflats.

Our mission for the day was to survey the natural plant communities and distribution in the marsh and determine suitable locations for water level loggers to gather data that would be used to aid in wetland restoration. Having never done this before, I had little idea of what to expect as we set out on the short walk through the woods to the marsh, with our loggers and the PVC drainage pipes I had drilled holes in the day before in hand.

Walking on marshes always proves to be a difficult task. The ground sinks under your feet, and small holes and pools can easily go unnoticed until your boot has slipped in. Navigating this uncertain terrain was not easy, especially not with our added baggage, but we persevered!

Morning at Little River Marsh in Georgetown

“It’s remarkable to me how nature always finds a way to work in the background, and you don’t really notice what is going on until you actually look for it... I hope my experience inspires you to think deeper about a simple marsh too.”

Sea Lavendar ~ Copyright ©2023 Marilee Lovit

As we went further into the wetland, searching for a good spot for our first logger, the natural beauty of a place that, at a glance, looks like an unexciting mass of plants with the occasional pool began to show itself. I was surprised with my first encounter with sea lavender, whose light purple flowers stood out against the rest of the marsh. In a small pond, we found a collection of tiny shells brought in by the tide. Dragonflies darted around us, and in the distance a few great egrets staked out their morning meal. Breaking through a row of cattails, we scattered a group of sparrows nesting in the area. As we approached our first site, a deer flicked its white tail and disappeared into the bordering woods. The wetland was full of life!

Our location survey culminated at a cluster of pannes, depressions in the marsh that retain water even at low tide. These areas host species that are more accustomed to saltier conditions and, in marshes like this one, signify a lack of proper drainage that impacts the health of the wetland, making them the perfect site for a logger to learn how the natural cycles of this marsh were functioning.

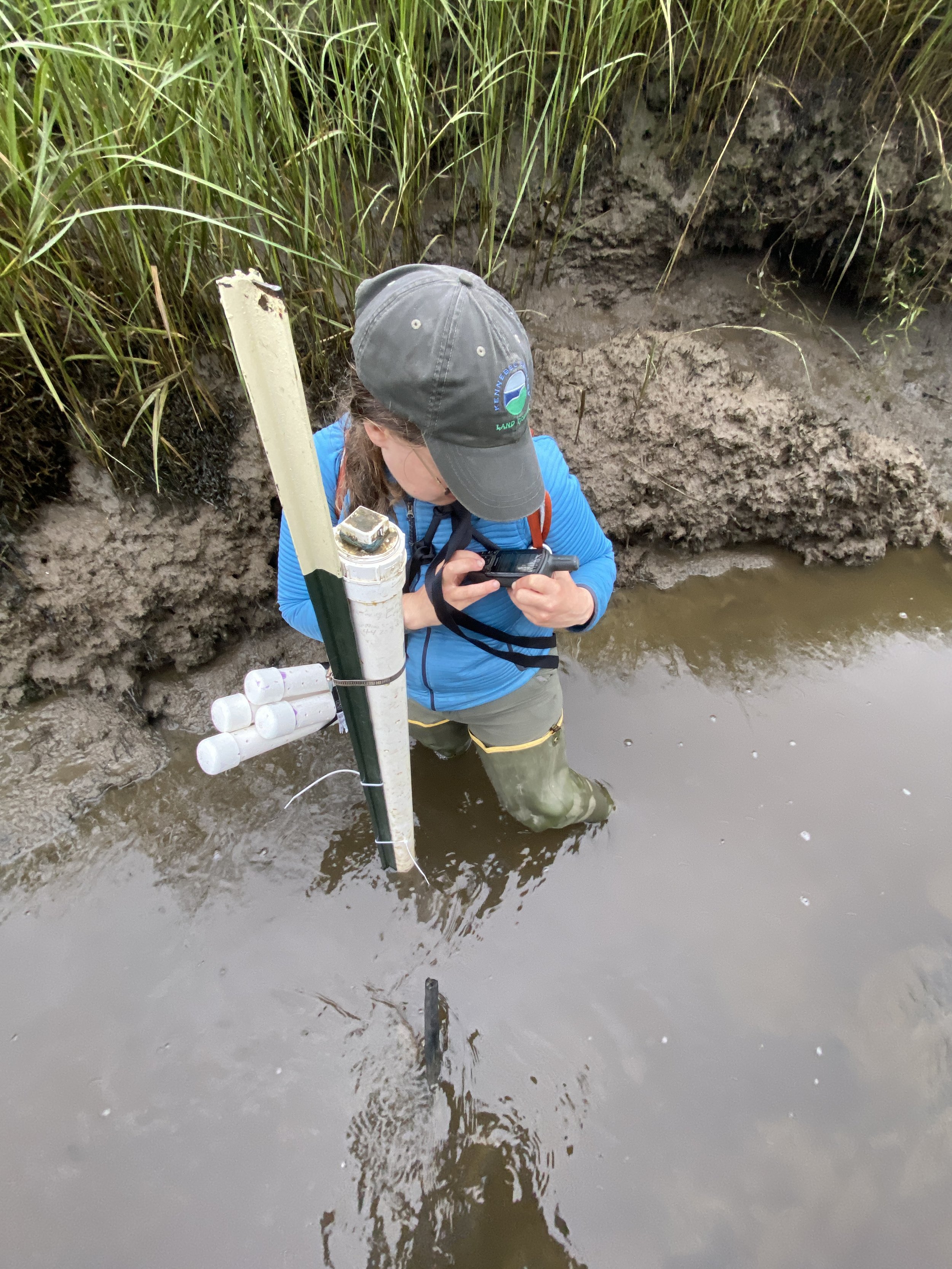

Water level logger in PVC casing installed in a marsh panne.

Installation, however, was its own challenge. Despite yielding under our feet with each step, the ground was less inclined to allow us to sink the pipes and loggers beneath the water level. Working against the roots, we finally broke through to the softer ground beneath and the pipe slid into place. One down, three to go.

On our way back across the marsh and towards our other locations, we documented the species in different locations, considering what the marsh might look like in the future and where restoration could be important. As we did, the gems of the marsh that we had found hiding earlier began to show themselves in greater numbers. As we plunged our third pipe below the surface, I noticed butterflies, previously unseen, fluttering seemingly everywhere. It was as if the wetland had decided to reveal its value to us as a way of encouraging our restoration goals.

The remaining pipe was uneventful, the easiest of the day, but that did not overshadow the appreciation I had gained for this complex environment. I can say with confidence that from now on, whenever I pass a marsh off the side of the road, I won’t ignore it. I will be thinking about the species diversity of the outwardly similar sedges, imagining the various animals that rely on the wetland for food and shelter. It’s remarkable to me how nature always finds a way to work in the background, and you don’t really notice what is going on until you actually look for it. KELT’s wetlands restoration work has helped me to appreciate the importance of these areas far more than before. I hope my experience inspires you to think deeper about a simple marsh too.